Wood and Cane Invalid Chair

Object

This post is looking at the background and treatment of a wood and cane invalid chair from Beamish Museum’s collection. The chair is a combination of a wheelchair and carrying chair which would have been pushed by an attendant rather than self-propelled, as evidenced by the height and position of its rear wheels.

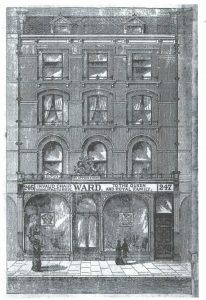

The chair was made by John Ward Ltd, which was one of several companies specialising in the manufacture of invalid furniture in the 19th and early 20th centuries. The industry had grown considerably from the 1790’s onwards, prompted by the Industrial Revolution, medical advances and increasing casualties from the Napoleonic Wars.

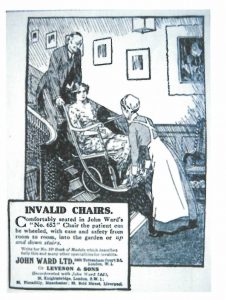

Despite the plaque on the chair, naming the design as ‘The Wardway’ and stating the patent has been registered, it could not be traced through the patent database; the term ‘patent’ often indicated construction novelties rather than actual official registration. The design of the chair allowed two attendants to carry the patient up and downstairs and a wooden pole would have been placed between the two arms in order to allow the patient extra security – this feature has been lost on the Beamish chair.

Wheelchair users were not commonly seen in public during the late 19th / early 20th centuries, something that may be attributed to their cost. A caned chair like the one from Beamish was certainly a cheaper alternative, though they still weren’t cheap as they ranged from four to five guineas. Such chairs were purchased by wealthier individuals for domestic use, hired, or used in institutions. Similar chairs were employed to improve the comfort and mobility of patients in domestic contexts, convalescent homes and in hospitals.

Condition

- Evidence of dust and dirt on the surface

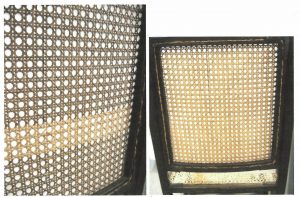

- The cane appears brittle

- There are areas of loss to the cane seat and back

- Areas of varnish have been worn from the wood

- There are some missing areas of the wooden frame, including a carrying handle

- The metal components have evidence of greasy deposits on the surface as well as dust and dirt

- The rubber has hardened.

Conservation

Although the greasy deposits seen on the surface of the metal components were arguable part of the history of the object, as they showed evidence of use, they concealed the surface and it was unclear how deteriorated the metal was beneath these deposits. As such, following testing of a number of treatments, they metal components were initially surface cleaned using a combination of cotton wool swabs with IMS and cotton wool swabs with a 50:50 solution of IMS/deionised water.

Following this, the wood was surface cleaned using cotton wool swabs with deionised water in order to remove the dust and dirt. There were a number of areas of wax and white deposits on the surface of the wood and these were removed mechanically using the end of a cocktail stick in order to improve the aesthetic appearance while not damaging the varnish.

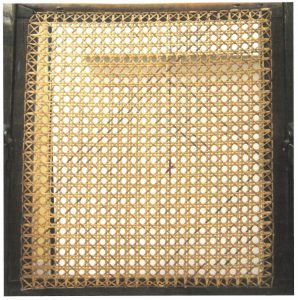

Whilst the majority of the dust and dirt on the cane is due to storage in a dusty environment, the soor-darkened canes on the reverse of the seat back are arguable part of the history of the object. However, this type of dirt increased the acidity of the material, which can cause deterioration, and so it was deemed acceptable to remove it. This was achieved by gentle brushing with a soft bristle brush into a low suction vacuum with gauze covering the nozzle, (which was applied to prevent potential areas of detached cane becoming lost). However, this treatment only removed the loose surface dirt from the cane, while the more ingrained dirt remained. As such, solvent cleaning was undertaken in order to remove this additional dirt layer. Cotton wool swabs with a solution of 50:50 IMS/deionised water were rolled over the surface and successfully removed the ingrained dirt from the cane.

The cane on the seat and back of the chair had several areas of loss and these needed to be addressed if the object was going to look functional. If the chair were being treated by a cane-furniture restorer, they would replace whole cane strands, or even possibly the entire seat/seat back. This would be appropriate if the furniture being restored was also required to be functional. However, as this is an object from Beamish Museum, the priority is to retain the original material and have the repair be sympathetic to the rest of the object, whist ensuring full documentation of the process so that repairs can be easily identified.

A square of white Plastazoate was used to support the cane during humidification; it was tied beneath the canes using cotton tape, which allowed it to be raised as the damaged sections of cane became flatter. An ultrasonic humidifier was used in order to locally raise the humidity of the cane and allow those areas to be gently straightened and flattened; this process took around 45minutes to complete. Any areas of surface condensation that were noticed during the humidification process were removed using dry cotton swabs. In order to allow the cane to remain flat overnight, a section of correx was tied beneath the seat.

It was decided to repair the gaps in the cane work with new cane as this would help to stabilise the brittle ends of the original damaged cane as well as restore the aesthetic to the object. As the new cane was far paler than the original material the decision was made to stain the new cane in order to help the new material blend with the original. Samples were immersed in coffee and two different strengths of tea for two hours. All of the samples produced a good colour match to the original, however the decision was made to use tea as there was less residual odour from this method.

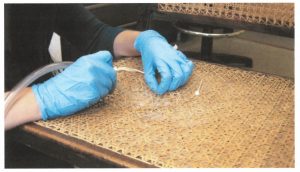

Sections of new cane were cut to size and the ends of the new cane strips were shaved down so that scarf joints could be created beneath the ends of then existing canes. The new cane was adhered to the old using 30% Paraloid B72 in acetone and clamped in place to create a strong bond.

Although the pole, which would have held a patient in place, was missing, it was decided not to replicate this piece as it was unclear exactly what it would have looked like. However the decision was made to replicate the missing handle as there was a second one that could provide the correct form. The original handle was unscrewed from the chair and a mould was made from it using silicon rubber. This mould was then filled with polyester resin and allowed to cure. Any gaps in the resin were filled using polyfilla in order to create a smooth, uniform surface. The cast was then colour matched using acrylic pigments to match the original handle. Modern hinges that were closest in form to the orignals were acquired and attached to the chair and the replica handle was then attached to the hinge. The original handle was then re-attached to the chair.