Egyptian Shabti

Object

After a bit of a hiatus from uploading posts we’re back and we’re starting with an interesting object; an Egyptian Shabit from the Oriental Museum which was treated over the summer.

The people in Ancient Egypt developed a very intricate set of beliefs around death with various forms of rituals as well as a very specific assemblage of objects. While these artefacts may be part of a standardized practice they can also inform us on the life of the deceased and the technological innovations in Egypt at the time of death. One such object is the shabti.

Found in great numbers in excavations, the shabti is one of the most common artefact collected in Egyptian tombs, and has, therefore, been highly researched and is found in a great number of institutions. It can be made of a variety of materials including wood, stone, and faience. They were supposed to accompany the deceased into the afterlife and act as their magical substitute, or servant, if they were required to do menial tasks, such as farming. Some sources indicate that there were two types of shabti: the slave, and the overseer. The latter would be holding a whip. The one here has two hoes and a basket, which could indicate it being a ‘worker shabti’. However, the hoes could also be interpreted as whips making it an ‘overseer’.

Shabtis usually have inscriptions on them including one calling upon the god of the dead Osiris, and a description of who the person was, or, at least, their title or job (ex: overseer, scribe, pharaoh etc.). The shabti that was to be conserved has such inscriptions, though they were not easily readable.

It readily resembles the style of the Third Intermediate period in Egypt, was catalogued as such by the Oriental museum, and has been identified of being from 1200 to 1100BC by Dr. Penny Wilson. Like many shabtis through time it is made of faience, a technique that emerged in Ancient Egypt at the end of the 5th Millenium BC.

Faience can be seen as the first high technology ceramic. It is composed of a core made of crushed quartz, sand, lime and binding agents that aid the shaping of the figurine. The core of the object showed many important inclusions of quartz as well as red-pink specks when observed closely under the microscope. As expected with the combination of the aforementioned materials, the core had become brittle and crumbled away while being in a beautiful state. This crumbling is partly due to the presence of soluble salts in the structure of the figurine, which exert pressure on the core walls and eat at it. These are introduced because of the make of the Egyptian soil, where the material is sources, as it is rich in salines. It is an internal vice that can be reactivated and accelerated if the core comes in contact with water. Treating the shabti for soluble salts was therefore out of the question as this would result in the total loss of the object. Additionally, calcareous concretions were observed. These can also affect the glaze around the core by creating cracks and weaknesses at the surface of the object or at the interface between the two materials.

Condition

- Broken into two pieces

- Evidence of failing past repairs

- Surface dust and dirt visible

- Excess adhesive on the surface.

Conservation

The shabti was first surface cleaned using a variety of dry cleaning materials in order to remove the dust and dirt. Following this the object was wet cleaned using a 75:25 ethanol deionized water solution and cotton swabs. The higher proportion of ethanol was chosen to ensure quick evaporation of the solution to reduce the exposition of the material to water. This solution affected stray bits of adhesive found at various places on the object making them flake off. These were then gently removed using a scalpel.

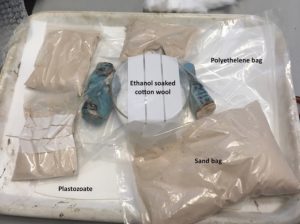

The third step was to take the old adhesive down. As recommended by the literature the shabti was put into a solvent chamber to soften the adhesive so as to ease the different pieces apart. The solvent used to saturate the atmosphere was ethanol as it seemed to be effective in the removal of the adhesive on the shabti during wet cleaning.

The artefact was put inside a clear polyethylene bag and as much air was removed as possible. The shabti was left for 15 minutes at first to ensure that the solvent rich atmosphere would not damage the core and glaze. Exposure time to the solvent rich environment was increased incrementally with regular checks of the softening.

Though the adhesive had softened after being in the solvent chamber the mend at the legs could not be lifted off. It seemed as though the adhesive had softened on the edges but not at the centre, creating cracks when a dental tool was used to try to ease the two parts apart. As a result, solvent was injected into the cracks and then dental tools were used to ease the various components apart.

The remaining animal glue was softened using appropriate solvents and removed mechanically, and the shabti was then consolidated in order to reduce flaking and to prepare the surface for readhering the fragments. 15% Paraloid B72 in acetone was injected into any cracks on the surface of the shabti, which would help to stabilise them. The fragments were then adhered using 30% Paraloid B44 in acetone.

As there were a number of areas of missing surface material, and the two halves of the shabti couln’t be adhered togehter in its current state, the decision was made to create a fill, which would allow the shabti to become whole. A combination of adhesive and microglass balloons were used as a paste and applied to the areas of missing surface material, which was smoothed to replicate the original surface of the object. This allowed for the two halves of the shabti to be adhered together.

Initially the fill was going to remain unpainted so that the area of repair could be identified. However it was determined that the fill was too distracting and so it was colour matched to the original glaze of the object.