Historic Silver Conservation – Student Post

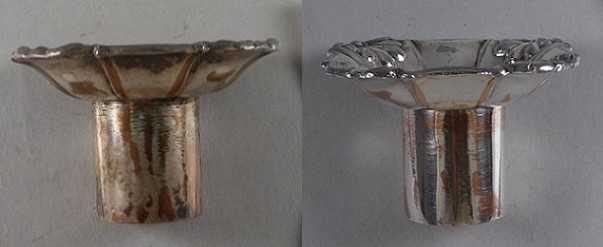

Amidst the soiled and corroded archaeological metals that we have been working on this term, we were given the chance to work with some historical metals. As one might guess, the difference in degradation, conservation methods and results between the two is quite large.

The objects were provided by University College (Durham Castle) and consisted of silver plated candlesticks with separate candlestick-tops, platters and posy bowls. They were all covered in a visibly discolouring tarnish and the candlesticks had remnants of wax on the surface. One of the posy bowls contained a green powdery residue on the interior bottom, which indicates the use of floral foam. This had left orange and black corrosion products. A number of candlesticks had an exposed bottom with highly corroded Iron and, in one of the cases, a type of cement.

The owners wanted the pieces to look ‘as good as new’ as they are regularly used at the castle. The standard procedure for these types of historic metal is to remove all tarnish and deposits, to give the objects their original shine and colour back. This is achieved by carefully polishing the surface until the silvery shine is obtained, after which a coating can be applied to preserve this shine and colour. Removing the tarnish could be seen as the removal of ‘original material’, as this layer is actually a chemically altered version of the metallic surface. Moreover, Silver tarnish is a stable layer that doesn’t cause any further harm to the objects. However, the value of these objects is largely dependant on their appearance. Historic Silver – or in this case Silver plated metal – is a largely decorative material and cannot be appreciated in the same way when the surface is distorted by tarnish. Therefore, removal is deemed necessary.

The first step in the treatment was to remove all large deposits such as wax and floral foam with wooden tools or soft brushes. An organic solvent was used to dissolve the tough and hard-to-reach remainders. To remove the tarnish, we used a microfiber cloth with a very fine abrasive solution and carefully wiped the surface, making circular motions. Some of the objects had very fine ornamentation which made it hard to reach the small crevices with the cloth. Small cotton swabs and soft brushes were used to polish these spots. The orange and black corrosion in the posy bowl was removed by using a slightly more abrasive treatment. When the right silvery appearance was reached, we cleaned the surface with acetone to remove all polish residue

Most objects were waxed after cleaning, while some of the candlesticks had an additional step. The corroded Iron, exposed in the bottom of the object, had to be stabilized to prevent further corrosion. This was done by applying a rust converter with a soft brush. The cement was injected with an appropriate consolidant of an acrylic copolymer, which was also used to coat the Iron and cement, as an additional protective layer.

The Silver surface was coated with microcrystalline wax. This was applied with the microfiber cloth, either on the cold metal or after heating the surface until it was hot to the touch. The wax was left for a short time to bond with the surface before being buffed with the cloth. On larger objects, such as the candlesticks, the coating was done in smaller sections, to make sure the wax didn’t dry out.

On objects that had been supplied with an accession number on the surface, this number was once again applied with black ink on a stable layer of a suitable acrylic copolymer. Finally, the treated objects were photographed and repackaged, to be sent back to Durham Castle.

Riva.