May ’18

Taxidermy Owls

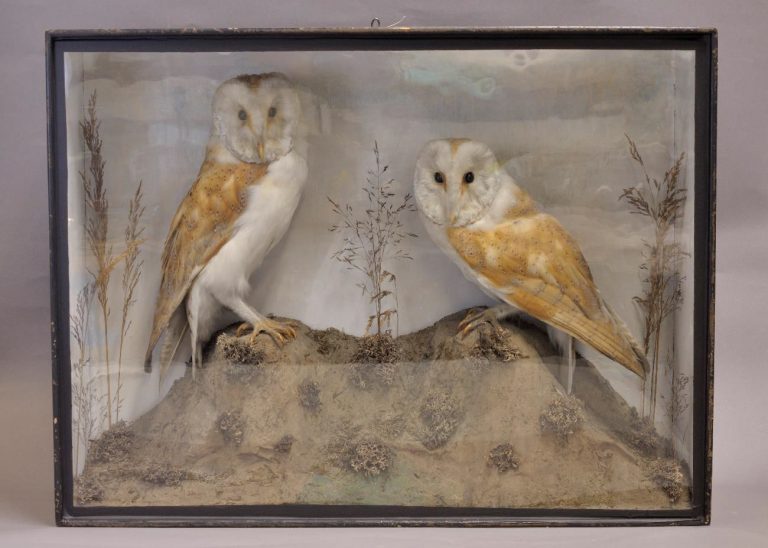

May’s ‘Object of the Month’ is a pair of taxidermy owls from Beamish Museum.

The practice of taxidermy involves removing the skin from an animal, followed by stuffing it with a filler material and positioning the specimen. The earliest surviving example of taxidermy in the UK is the African Grey Parrot which belonged to the Duchess of Richmond from 1702, which she had stuffed after it died. Most early examples do not survive because taxidermists had not yet devised a proficient enough method for preventing insect damage. It was not until the development of arsenical soaps, developed by Bécoeur in the eighteenth century, that there was an increased survival rate for taxidermy specimens.

Animals which were displayed for scientific reasons were placed in relatively static poses and had no context as they were simply for study. In the nineteenth century, museums started using dioramas for taxidermy specimens in order to better showcase the environment an animal had come from. Taxidermy entered the public sphere in the UK after the Great Exhibition in 1851 where taxidermists would showcased their talents to a wide audience who would then buy their objects for home display. However this popularity only ran up until around the beginning of the First World War when the demand for such items was no longer deemed important. The personal interest in taxidermy never fully recovered as stuffed animals no longer had the scientific meaning which they had for naturalists.

The barn owls from Beamish are an example of a Victorian display item which is no longer as commonly used. Easier access to photography and images of animals makes it less necessary to have an actual example on our shelves. In modern society the killing and stuffing of animals is often seen as cruel, and has a negative effect on their populations. The barn owls are evidence of social change since the Victorian period, especially when displayed in a living museum like Beamish, which seeks to replicate Victorian life.

Conservation:

The case exterior, after significant testing, was initially surface cleaned using smoke sponge in order to remove dust and dirt. Smoke sponge provided the same visual level of cleaning as Groomstick and Akapad, but was much easier to handle and use. The glass of the case, once removed from the frame was cleaned using an equal mixture of ethanol and deionised water with a few drops of Synperonic A7 to remove dust, dirt and grease. It was then wiped using a lint-free cloth dampened with deionised water followed by a dry cloth to prevent water marks. Wet methods were more suitable than dry cleaning because they could solvate the residue from the old gum tape, making it easier to remove.

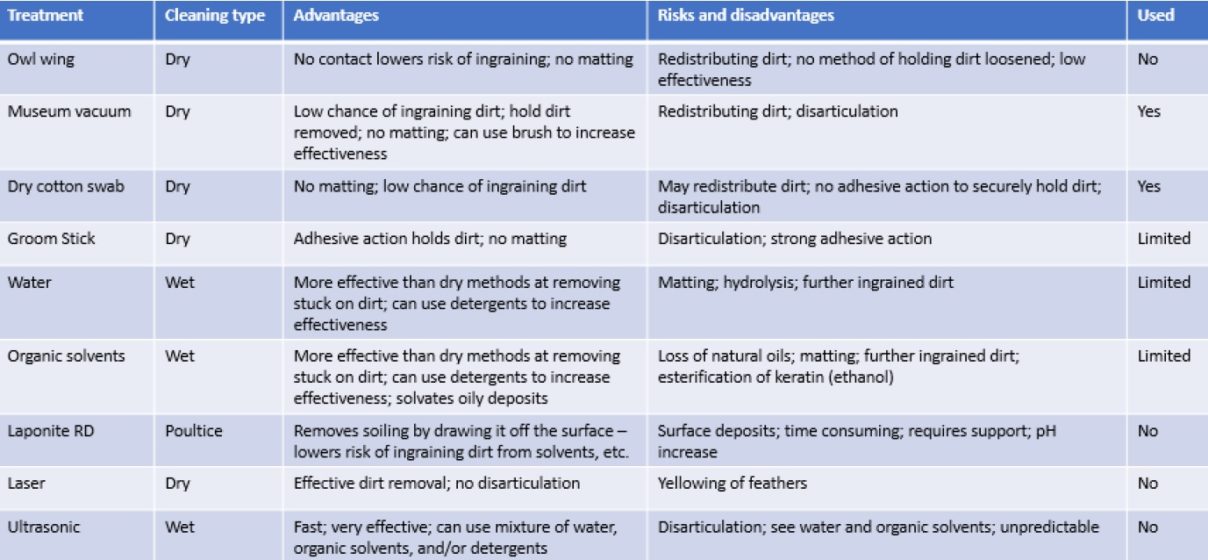

A variety of different cleaning methods were considered for removing the dirt and soot from the barn owls; these were tested from gentlest to most interventive. Initially the barn owls were vacuumed to remove the loose dirt and soot. Following this a combination of wet cleaning and dry cleaning methods were implemented depending on which areas of the barn owls were being cleaned. Groomstick, for example, despite being effective at removing dirt was unable to be used on areas where the feathers appeared slightly loose. Water and other solvents were only used in areas where the dirt was adhering to the feathers.

Organic material on the diorama were found during cleaning to be only loosely adhered, meaning they were picked up in the filter on the museum vacuum. Laponite RD gel was tested as a cleaning method for these areas, but it still removed the organic material meaning it was no better than the vacuum. The solution was to collect the material picked up in the filter used on the vacuum and replace it afterwards in the case. This meant it was not able to be returned to the exact position it was removed from, but no additional material was added and the original material was returned, so this was thought to be the most ethical choice.

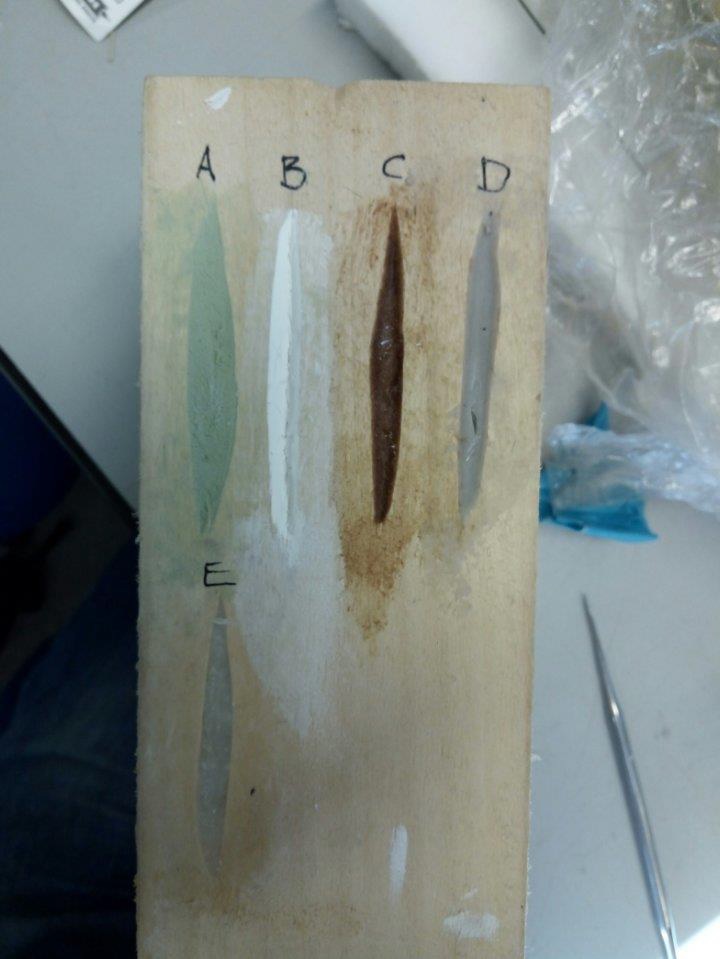

During initial investigation it was found that there was a large split in the wood on the back of the case, which would require filling if the case was to be as airtight as possible and prevent possible infestation. A number of different materials were tested and were examined for their reversibility, flexibility (so they could move with the wood), shrinkage and ease of use. Acrylic gesso mixed with calcium carbonate was eventually chosen to fill the gaps as it can be removed by physical means, and this is made easier if it is softened with water.

There was some difficulty colour-matching the inside of the case using acrylic paints as they were not as easy to blend as the original colours. Eventually an acceptable colour match was made using several different colours and blending them.

Stay tuned for next month’s object!