On The Cutting Edge of Conservation – Student Post

On the first day of our summer term we were tasked with the conservation of objects from local museums. The selection included a range of objects from African masks, to broken toys and weapons. We were dutifully informed that we may choose one object from the selection and that we would be anonymously assigned the other three objects.

Owing to my own morbid curiosity and never one to turn down a challenge I went for a sinister looking Amputation Kit. The object had evidently peaked interest in others as a heated bidding war ensued.

I came out victorious and an initial assessment of the object followed. It was in an extremely poor state; the mahogany box was broken down the spine, splitting the lid away from the base. The inner tool tray was also completely detached – something that I discovered with horror some days later. All of the tools were showing signs of corrosion. The lock was missing its key and the fastenings had been lost during its life-time. The velvet lining of the box was ripped, stained and infested with the remnants of a small, multicultural, civilisation of insects.

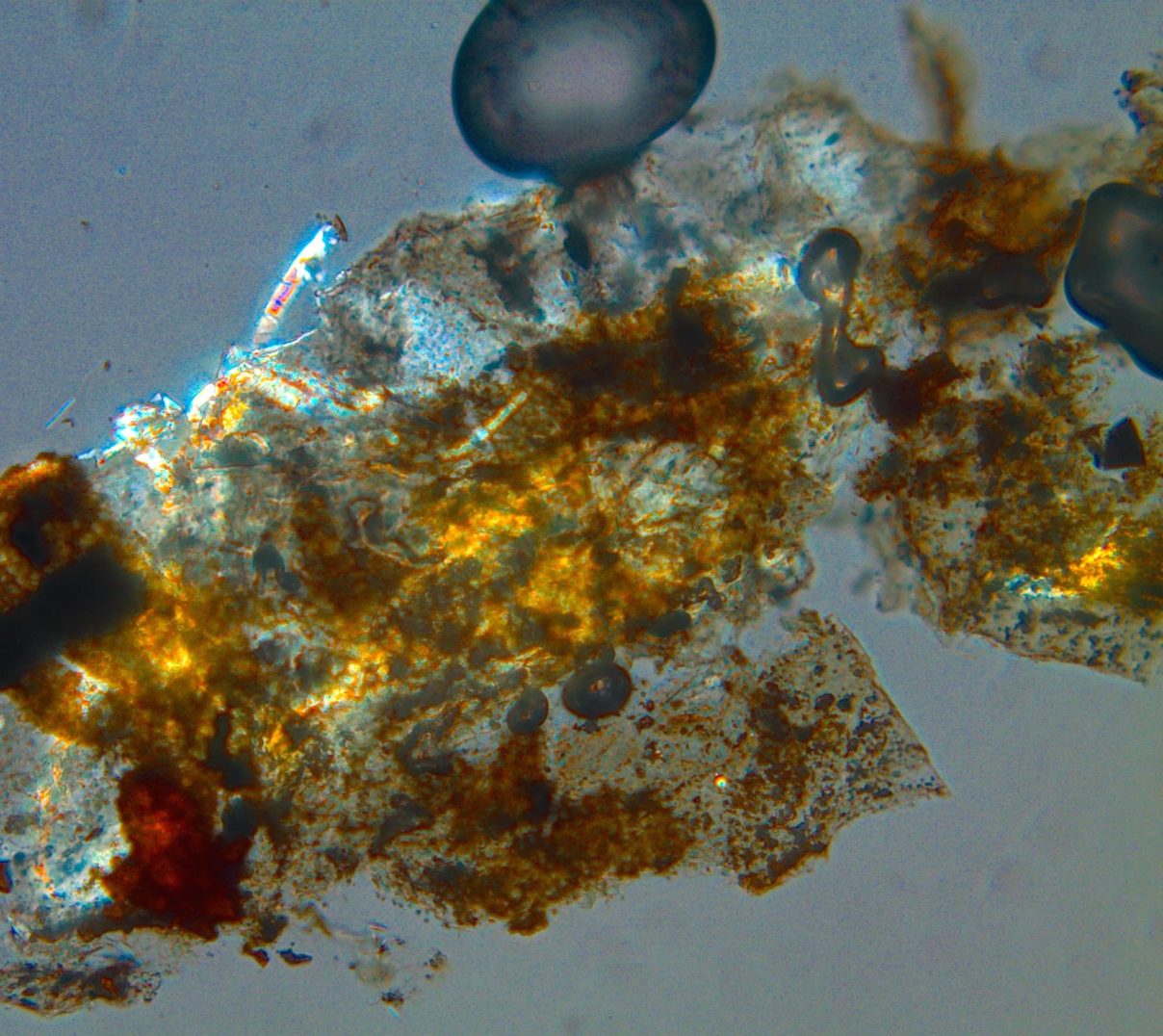

As with any object, all of these materials had to be analysed and diagnosed individually. Evidently the corrosion had to be removed from the knives but decisions about the course of action were halted by the discovery of what looked like tissue within the serrated blades of the largest tools in the set; the Amputation Knife and the Box Saw. After a short break and a strong, sugary, cup of tea the investigation of these materials took place. What could it be, surely not traces of skin or bone? The kit dates from 1820 and was used until the mid-nineteenth century. Could there really be evidence from an operation that took place some 150 years previously? My own toolkit was meticulously cleaned and I dedicated my afternoon to removing samples for analysis. While it is yet to be confirmed, it is highly likely that the sample is collagenous.

The Amputation Knife also has some staining along the blade. This is to be tested using Haemastrips – paper strips used in urinalysis to detect the presence of blood in urine. The analysis of these elements will confirm that the kit was used. There is also something to be said about the state of 19th Century medical practices with the presence of evidence from its final operation.

* * *

Part of the conservation process is investigating the history of the object. Luckily Beamish Museum had a significant amount of information about the kit. Accessioned to them in 1971 by Dr. J. C. Arthur O.B.E and Dr Katherine M. Arthur from their Medical practice in Gateshead. The toolkit was given to them by the previous proprietor, Dr W. H. Davis, when they took over the practice in 1930. Dr. Davis, his father and grandfather had operated in and around Low Fell and Wrekenton since 1830. Conveniently, the name “Dr Davis” is written along the spine of the box.

The kit itself was likely manufactured in Newcastle. The tools all display the name “Battensby”. John Battensby, a cutler and a surgical toolmaker registered to have been working in Newcastle between 1821-1829. Many of the kits manufactured around this time were manufactured for colonial import and were used heavily during the Civil War. However, it is highly likely that this kit would have been used locally for mining and farming accidents.

* * *

The conservation of such an object is intimidating. It requires the complete reconstruction of the box. Ethically this is regarded as one of the most significant tasks, as the box was made to protect the tools as well as emphasising the quality and craftsmanship involved within its manufacture. The removal of the corrosion on the tools will ensure that they last for perpetuity as an example of medical practices during the 19th Century.

Jess.